The Duke of Marlborough Is Dead

Almost two weeks ago the Eleventh Duke of Marlborough, John G.V.H. Spencer-Churchill, died. The Daily Mail includes numerous photos from the funeral procession last week.

Possibly best known for his award-winning gardens, he resurrected Blenheim Palace and transformed it into a (profitable, we’re told) modern tourist attraction. Unfortunately I missed the opportunity to meet the 11th Duke at the Marlborough: Soldier and Diplomat book launch at Blenheim Palace a few years back. My wife and I were, however, able to visit the Palace on our own. We saw the Blenheim Tapestries pre-restoration, and there was some sort of exhibit about some obscure descendent of the First Duke who managed to make a name for himself in government or something. But that’s post-early-modern, so let’s not dwell on it.

If you’re interested in seeing the famous Victory Column, it’s away from the main Palace building over a bridge, and you have to thread your way into a minefield of sheep droppings. But if you do persevere, the First Duke himself will greet you from atop the column:

Hopefully the 12th Duke of Marlborough will manage the UNESCO World Heritage Site as well as his father did.

All of which provides an odd (and hopefully not too-inappropriate) segue to how the rumored death of the First Duke of Marlborough was received by his French foes. Marlborough s’en va-t-en guerre, the melody which the English later appropriated for their For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow, was penned after false rumors spread that Marlborough had been killed in the battle of Malplaquet in 1709. The words focus on how his wife Sarah received the news.

A relatively close English translation of the lyrics from Wikipedia follows. (The Wordsworth translation adds new lines to the spartan original French version in every verse).

- Marlborough has left for the war

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

Nobody knows when he will come back. - He will come back at Easter

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

Or on Trinity Sunday - Trinity Sunday goes by.

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

Marlborough does not return. - My lady climbs up her tower

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

As high as she can climb. - She sees her page coming

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

All clothed in black. - “Good page, my good page”

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“What news do you bring?” - “At the news that I bring”

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“Your pretty eyes will start crying!” - “Take off your pink clothing,”

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“and your embroidered satins!” - “My lord Marlborough is dead”;

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“he is dead and buried.” - “I have seen him borne to the grave”

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“by four officers.” - “One of them carried his breastplate”

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“another his shield.” - “Another carried his great saber”

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“and the last carried nothing.” - “On his tomb was planted”

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“a beautiful flowering rosebush.” - “When the ceremony was over”

Mironton, mironton, mirontaine

“Everyone went to bed.”

[The web suggests this mironton… was nonsensical, used for the sounds, and not referring to the beef-and-onions dish.]

You can find various audio recordings on YouTube and CDs, including this version. In the late 18C it was resurrected as a French nursery rhyme, made popular by the peasant wet-nurse who looked after Louis XVI’s infant son. This Louis XVII conveniently died in 1795 before the French Revolutionaries could agree on what to do with him.

See what happens with History? You start out talking about the 21C death of a British aristocrat and end up with the death of an 18C French would-be-king. The First Duke of Marlborough would probably have found that amusing.

Citations as window to the discipline’s soul

A recent blog post on Poor citation practices continues the long-standing pissing-contest between the Two Cultures (or is it Three now? maybe Four?). As its title suggests, the author thinks that the relatively small number of citations in social science and humanities publications translates into ‘self-harm’ for these flaccid disciplines that lack voluminous citations.

In previous posts I’ve expressed my own dissatisfaction with how historians discuss (or don’t discuss) historiography, and I’m enough off a splitter to cry out for more citation, even if publishers (and some readers) prefer otherwise. So in general I’m sympathetic to blog post’s overall appeal for greater citation.

There’s also a very interesting table of how citations facilitate some of the fundamental ‘features’ of scholarship, halfway down the post.

So I don’t have any particular insight into the question of comparative citation counting, other than a warning (and question) about automating the process. (And to point out that the focus on journal’s h5 scores are pretty pointless for historians, since we’re much more likely to cite books and book chapters than journal articles – maybe the fact that there are so few thematic History journals plays a role?) The author, writing from a social science perspective, praises Google Scholar Metrics for providing a “very inclusive” counting of citations. Not so much for History, if my book is any indication. Because I’m generally a vain individual, I keep track of which publications cite my work. So when I search Google Scholar Metrics for my Vauban under Siege book, I find 14 works that cite it. Which is great, except for the fact that there are at least 25 works that I know of which explicitly cite my book – almost 80% more works than what Google says. If I cared, I’d track down which ones are missing, though I’m guessing some of them are probably book chapters and non-English works.

Admittedly, the citation count of my 2000 Journal of Military History article on Ramillies is much more accurate: 14 citations compared to the 16 that I’m aware of. But since History is all about the books, Google Scholar is hardly acceptable for History, at least as it stands. But perhaps this is only to be expected, given how historians are constantly forced to deal with the kind of messy information that Google tries to engineer a solution to.

Anyone else have better luck with Google Scholar? For that matter, do any historians actually use Google Scholar with any frequency? I’m constantly underwhelmed every time I try to find additional secondary sources using it. Searching Google Books and the web is usually a much better bet.

Elizabeth’s wars

Just finished teaching my Elizabeth I section in Tudor/Stuart England. As usual, it’s hard for students to keep straight all the pertinent historical details when reconstructing a narrative – most of the places, people and events are new to them. The same is true for me as well, since almost every course I teach covers at least two centuries (and usually more than one country), which means I teach hundreds of narrative arcs from one year to the next, and frequently have to jump from England to France to Spain to Germany to Italy and beyond. Last time I taught Tudor/Stuart was 6 years ago, with a lot of other periods, topics and countries in between, so it’s been awhile since I delved into the Tudor details.

Preparing for these lectures, then, I rediscovered that historical narrative is, for me at least, one of the hardest ‘types’ of historical knowledge to remember. You can create broad narratives of various thematic topics by, for example, remembering that the ratio of pike to shot gradually declined over the course of the 17C and then rapidly disappeared by the time of the War of the Spanish Succession. There are very few moving parts, if you will, in such stories. And such thematic developments are also relatively simple to explain: maybe it’s about the gradual increase in the rate of fire and the improved accuracy of the weapons, etc. Of course there are far more complications if you start to explore the details, as Bert Hall’s Weapons and Warfare in Renaissance Europe suggests, or if you start comparing specific countries and theaters, or consider the possibility that the “progress” from pike to musket isn’t necessarily linear or inherently moving from less effective to more. But most people, even historians, tend to remain at the much more generalized level. And there usually isn’t that much variation from year to year, or, if there is, we tend to focus and expect linear progression that smooths out the variations over several centuries. In other words, we’re generally interested in the trend line rather than the specific events in the dot plot. Individual cases will be chosen because they are deemed representative of the larger trend.

But then we’ve got political and diplomatic and military narratives, which are a bit more complicated because they almost always focus on the specific events themselves, rather than the trend line – a lot more data, and a lot more connections between the points. We can certainly generalize from these narratives to create a thematic argument, e.g. one could argue that Elizabeth’s wars were driven (from the English perspective) by a combination of religious conflict, unstable and potentially hostile neighbors, and economics: Catholic internal and foreign plots + English desire to support the Protestant International + instability and foreign influence in Scotland and Ireland + inviting Spanish overseas trade…. That’s relatively simple, and most early modernists are familiar with such an argument, and it’s an important question to discuss. But we really need to have a handle on the narrative of what actually happened as well. It’s quite another matter to remember the order in which specific events occurred, particularly when there are dozens and dozens of events, each of which was precipitated by other events, and which in turn might precipitate other events.

Admittedly, we could keep it really simple: England fought two wars in the 1550s and 1560s against France but lost their last continental foothold of Calais nonetheless; they also had the occasional intervention against faction-riven Scotland, and from the 1560s on sent support to the French Huguenots and Dutch rebels, becoming directly involved in the war against Catholic Spain (fought in the Netherlands and at sea) from 1585 to the end of Elizabeth’s reign, along with more serious intervention in Ireland during the Tyrone rebellion (the original “Nine Years War”). This might be enough for a very general understanding of the period, though it’s a purely descriptive summary of English military involvement.

Yet as most of us who teach know, most historical textbooks (at all levels) tend to focus on what I’ll call event narratives (suggestions for a typology?). Especially if you’re focusing on English history, or use English-authored works. And that’s where it gets complicated. One option is to focus on particular key individuals. Take one example: the role of Mary Queen of Scots in English foreign policy. So you need to know who she was in the context of Anglo-Scottish-French relations: infant daughter of Scottish King James V (who died, possibly of despair, right after the English crushed his forces at the battle of Solway Moss); an infant princess whom Henry VIII tried to coerce into marriage with his son Edward, aka the Rough Wooing, before she was married off to the French prince Francis, thanks to the connections established by the ‘Auld Alliance’ between France and Scotland; a young Scottish-French princess then Queen consort raised at the French Court under the influence of the ultra-Catholic Guises, widowed in 1560 and returned to Scotland, where “her” kingdom had been ruled by her French mother Mary of Guise, but which was now being Calvinized thanks to John Knox et al (Calvinist missionaries who’d learned their theology in Geneva, and would eventually found the Presbyterian church in Scotland); a queen of Scotland who within 6 years would be forced to abdicate to her infant son James VI (raised by Protestant regents) and flee to England, which made things difficult for her cousin Queen Elizabeth, because various Catholics (English and otherwise) hatched plots to eliminate Elizabeth and thus put the next in line, one Mary Queen of Scots, on the English throne, and hopefully reCatholicize England as a result, an outcome Anglicans had feared ever since their last Queen (Mary) married Philip II of Spain and burned a couple hundred Protestants at the stake. Several plots later (one of which saw the defeated rebels flee to Scotland for refuge, which precipitated another English intervention), Elizabeth finally conceded that Mary’s continued existence served as an inevitable center for intrigue, and she was executed. But of course Elizabeth would die without issue, and the now-grown King James VI of Scotland would end up inheriting the English throne as James I of England, leading to a personal union of the two crowns. Any questions?

And that’s just a simplified version of the Scottish-French angle (admittedly leaving out most of the Scottish and French details) for only the first half of Elizabeth’s reign, with only the most proximate causes mentioned and all the juicy bits about murdered husbands and Virgin Queens left out. We should probably include the Cecils and the Dudleys, and we might as well talk about English relations with Ireland and Spain while we’re at it. Damn that web of history!

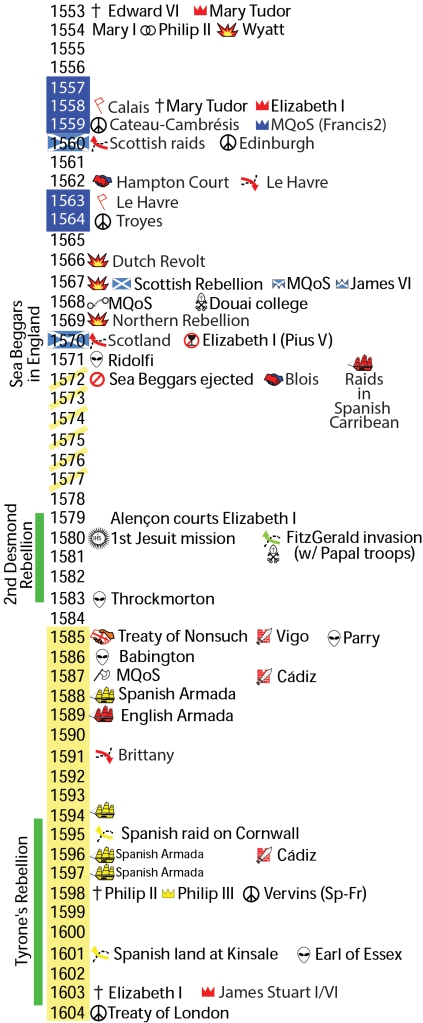

Fortunately there have been some very good books published on the subject – I’d recommend Paul Hammer’s Elizabeth’s Wars in particular. Such works made it relatively easy to create a reference timeline to track key events. Assuming you are driven to invest the effort needed to create such timelines, that is. Personally, I came quite late to the utility of timelines, since I was always underwhelmed with the boring two columns found in most books, and, frankly, I tended to think more in sweeping thematic arcs. (Probably the opposite of why many history buffs fall in love with the subject.) Perhaps as a result, one of the big lessons I drew from my graduate school experience was that thematic arguments about the Military Revolution and the like were worth little unless you knew the background narrative. Why such practices and technologies evolved the way they did might even have something to do with when, where and how specific countries fought. Such historical minutiae might, for example, explain why a country might make no “progress” in the military art for 50 years if it was, for example, fighting a particular kind of war (say a civil war) in a particular kind of theater. To mention just one specific example, recent research on early modern fortifications offers very local reasons for the uneven adoption of the trace italienne.

I only began creating linear chronologies when I started teaching full-time, but I’d like to think I’ve caught up and even made one or two improvements to the genre. But you can decide for yourself, if you want to compare the examples I post here (and in previous posts) with the historical timelines in Rosenberg & Grafton’s Cartographies of Time.

So here’s the “simple” version, though it could certainly be made simpler.

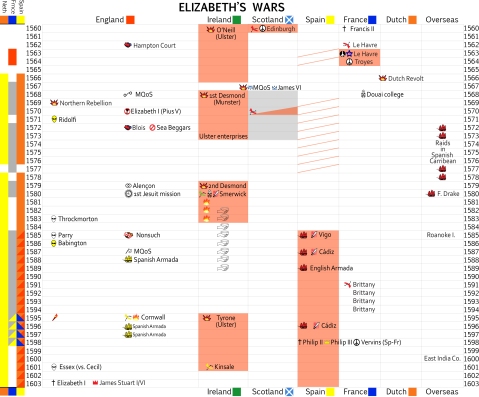

Here’s the more complicated version. As you can tell, it’s framed from the English perspective (in the large English column, domestic events to the left and foreign-influenced events), with an indication of when England was involved with various wars (the shaded semi-opaque red areas, with each country its own column), but it also tries to give a general sense of the other wars western Europe was engaged in (the narrow columns on the far left).

The above timelines are obviously at the highest, strategic, level. Which means they don’t include any operational details about the wars themselves, other than the occasional mention of a fortress surrendering. That would require a whole separate timechart, or else one in which you drill down or click on links.

My timeline philosophy, then, emphasizes:

- Efficient layout: use as many of Bertin’s variables as possible.

- Consistent iconography: see the blog page on my most frequently used Symbols. I try to use orientation and fill to record additional information. Icon symbols replace words, which means there’s more space and you can quickly skim for shapes (battles, plots, deaths…) rather than having to distinguish event words from all the other words.

- Consistent colors: I use specific colors for each country, and maintain that throughout all the visualizations.

- Consider creating both a detailed and an abbreviated version of the same timeline – particularly useful for teaching if you want to simplify things for the students.

Recent Comments